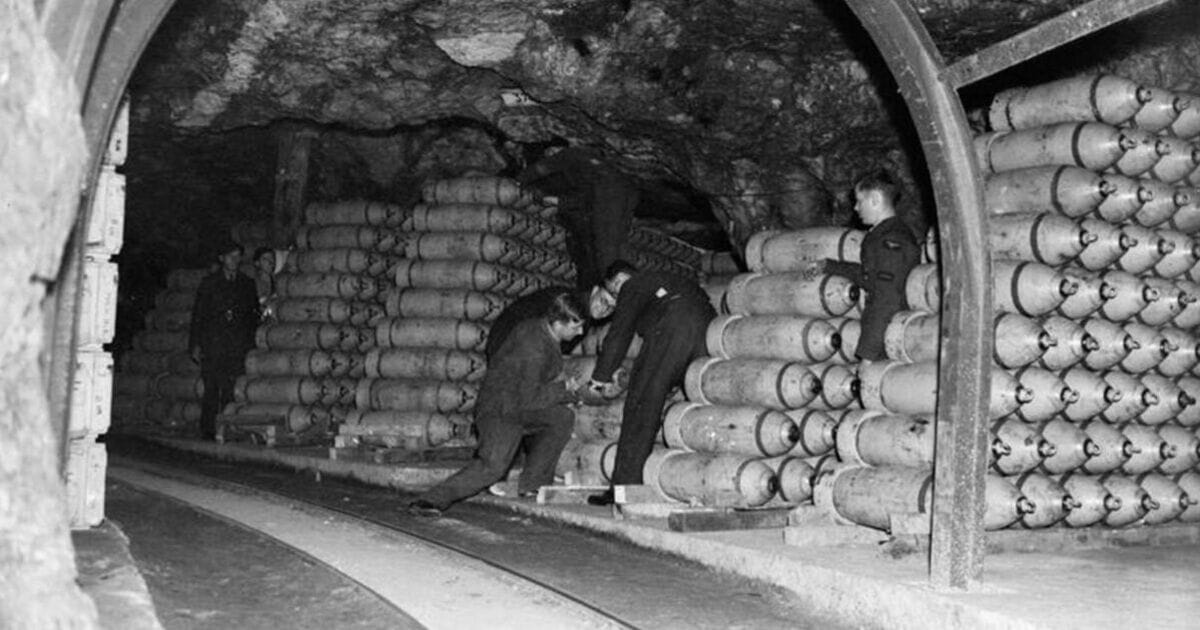

Thousands of tonnes of high explosives were stored in ‘The Dump’ (Image: Alamy)

On the very night 4,000 tonnes of high explosives obliterated a farm and nearby homes, Nazi radio propagandist Lord Haw-Haw taunted the British public that the devastation had been caused by one of the evil regime’s new V2 ballistic missiles.

Instead, the cause was an underground accident in RAF Fauld, a munitions storage depot east of Hanbury in Staffordshire. At least 70 people died in what was the largest explosion on UK soil and one of the largest non-nuclear blasts in global history.

Yet for decades its scale was kept secret and the crater left behind – an incredible 100 feet deep and 200 yards wide – was roped off from the public. Gypsum and alabaster had been mined under the rolling farmland since Roman times and in the 19th century demand had grown for plaster from the building trade.

Horizontal drift mines were tunnelled into the Stonepit Hills near Fauld. In 1937 the RAF bought 38 acres of the tunnels to store bombs and ammunition.

Eventually, 24,000 tonnes of high explosive bombs, plus incendiaries, detonators and up to 500 million rounds of small arms ammunition, were housed there for distribution by rail around the country’s wartime airfields. Fauld also acted as a repair centre for defective and jettisoned bombs.

READ MORE The brave World War 2 botanists who starved to death to save life-giving seeds

Aerial view of the huge crater left by blast (Image: Alamy )

No 21 Maintenance Unit RAF Storage was known locally as The Dump. While shrouded in secrecy, by 1944 more than 1,000 people were employed there, both RAF and civilian personnel, and nearly 200 Italian prisoners of war.

An underground railway was even built, linked to sidings across the River Dove. At 11.11 am on November 27, 1944,

the rural peace was shattered by two explosions in quick succession. Blue skies were hidden by plumes of black, greasy smoke resembling a mushroom cloud.

The ear-splitting blast was reportedly heard 30 miles away in bomb-damaged Coventry, while a shudder was even felt 120 miles away in Weston-Super-Mare. The tonnage which detonated at Fauld was twice that dropped on Coventry during the 1940 Luftwaffe blitz.

Upper Castle Hayes Farm was obliterated and three more farms extensively damaged, along with adjacent cottages, Hanbury village, the Cock Inn and lime works within a circular mile. A nearby reservoir was breached, swam-ping the devastated Ford plasterworks which was engulfed by six million gallons of water, mud and debris.

More than 1,000 acres of farmland were laid to waste and 60 homes were damaged five miles away in Burton. Munitions worker Joseph Foster recalled years later: “There was just one tremendous roar. The whole face of the landscape was different. Hayes Farm had completely disappeared.”

On Monday, 27 November 1944 between 3,500 and 4,000 tonnes of ordnance exploded (Image: Alamy)

Valerie Hardy, an eight-year-old at school that morning, said: “We heard this enormous bang. People didn’t know what was happening. The teacher settled us down and the next thing I knew my father had phoned the school to explain.

“He had been walking up the drive of our farm, about half a mile away from Fauld, and suddenly there was this blast. He turned around to look and saw this great mushroom cloud – the sky was dark.”

RAF personnel and the local mines rescue group battled flames in the maze of fractured tunnels, well aware that a stockpile of 10,000 bombs lay perilously close to the blaze. Not a single Hanbury home had escaped unscathed and the village, deprived of power and water, was cordoned off to deter sightseers.

Joseph Salt, given a George Medal for his rescue efforts, praised the Women’s Voluntary Service for feeding the village from mobile canteens: “They saved us.” As no records were kept monitoring the precise number of workers at the facility, the death toll remains uncertain.

The official report stated 90 were killed, missing or injured. They included 26 killed or missing at the RAF dump – RAF personnel, civilian workers and some Italian PoWs, five of whom were gassed by toxic fumes. At least seven workers were vaporised at Upper Castle Hayes Farm and a further 37 died in the explosions and subsequent flooding at the nearby gypsum mine, plaster mill and surrounding countryside.

Rescue worker Arthur Harris’s deep knowledge of the site allowed him to rescue people and keep returning to help further. As he went down into the crater one last time there was another explosion. He never came out.

At least 18 bodies were never found. A local relief fund made payments to victims and families until 1959. Two hundred cattle were also killed by the explosion. Some live cattle were removed but were found dead the next morning.

Another witness wrote: “Fields were littered with the carcasses of dead livestock and fish – as if Hanbury had been levelled by a Biblical plague.” On-site casualties could have been higher but natural and man-made barriers in the tunnel system helped contain the effects of the explosion, although toxic fumes seeped into adjoining mines.

A Coroner’s Inquest held in Burton-on-Trent into the civilian deaths recorded that they were accidental, caused by an explosion whose “origin was unclear”. The cause of the disaster remained top secret as the British government did not want the enemy to know the extent of the damage or to damage Home Front morale.

Embarrassment over the flawed operation of the dump may have been a factor. An RAF Court of Inquiry kept under wraps for 30 years found the site had suffered staff shortages with one management position empty for a year, while 189 Italian PoWs had little or no experience of handling explosives.

No 21 Maintenance Unit RAF Storage was known locally as The Dump (Image: Alamy )

There were also equipment shortages, a lack of worker training, multiple agencies in the mine compromising the chain of command, and safety regulations overlooked due to government pressure to increase work rate for the war effort.

It was not until 1974 that it was finally revealed the initial spark had probably been caused by a site worker removing a detonator from a live bomb using a brass chisel rather than a wooden mallet. Much of the storage facility was annihilated by the explosion, but the site continued to be used by the RAF for munitions storage until 1966.

By 1979 it was fenced off, and the area is now covered with more than 150 species of trees and wildlife. Access is restricted as a significant amount of explosives remain buried. A stone memorial was unveiled in 1990.

Valerie, who became a local author, said in a 2021 interview: “The Second World War came to our village of Hanbury with terrifying suddenness and had a profound impact on the whole community. I can remember standing with my sister at the edge of an awe-inspiring crater resembling the Somme battlefield.”