Archaeologists say they have gained new insights into the Maya ‘Snake Kings’ who ruled parts of Mexico, Belize and Guatemala around 1,500 years ago.

They say newly discovered stucco reliefs at a site that may have been linked to human sacrifices show the ‘celestial ancestors’ of the Kaanu’l dynasty. Dynastic snakehead emblem glyphs at other sites also refer to these so-called Snake Kings and Queens.

This once-powerful dynasty became a dominant force – rivalling the equally powerful city-state of Tikal. It’s thought that these ‘Snake Kings’ even managed to defeat and control Tikal at various points in history.

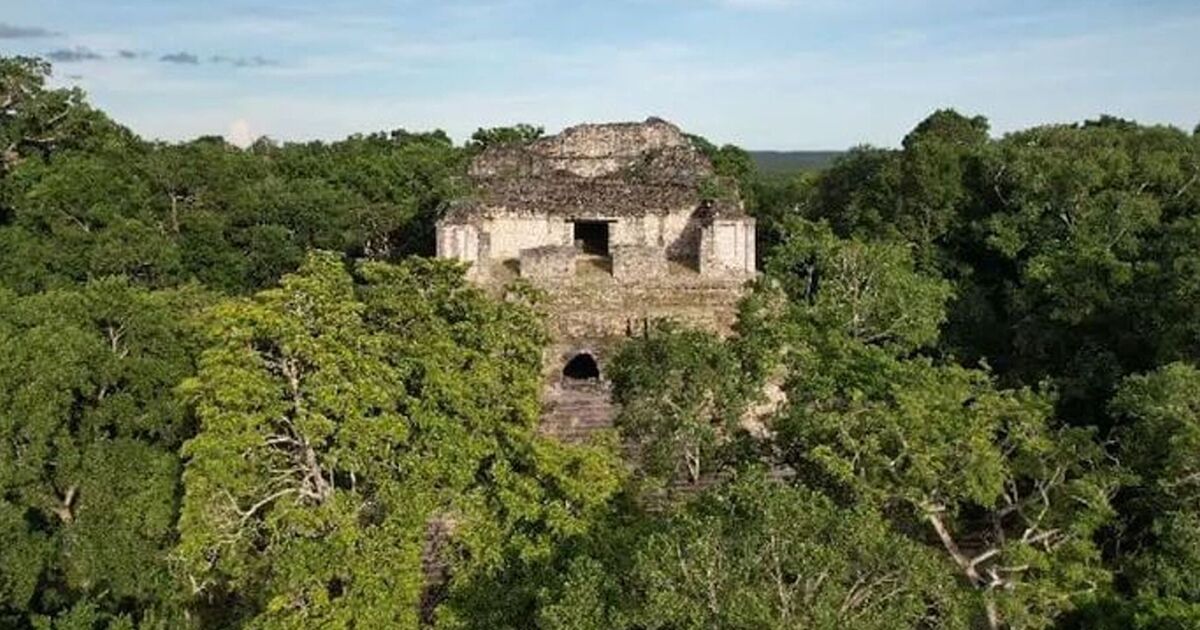

The Kaanu’l are best known through inscriptions and archaeological discoveries at Calakmul, near the Guatemalan border, and other sites – where the stories of these rulers were documented in hieroglyphic texts. Now, archaeologists have found new evidence of the Snake Kings, at the Maya city of Dzibanché, in Quintana Roo, Mexico.

The stucco reliefs are believed to be the Early Classic period – around 500-600 AD – which is potentially towards the end of the Kaanu’l dynasty’s 400-year reign. The three scenes formed part of the platform for a Maya ballcourt, where the city’s inhabitants would have played a ceremonial ball game – which archaeologists say were sometimes linked to human sacrifices.

It’s thought a central part of the displays may have been removed at a later date, by the city’s residents, presumably after the dynasty collapsed in approximately 650 AD.

The National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) said in a statement that the discovery offers “new insight.” A spokesperson said the scenes gave “new clues about the power of the Kaanu’l”.

The INAH statement reads: “The first scene shows two guardians who surround a pedestal on which, in pre-Hispanic times, a sculpture must have been placed; the particularity of the podium is that it incorporates glyphs alluding to a ruler of the Kaanu’l dynasty.

“In the second, there are images of individuals who – according to the epigraphist and independent contributor to Promeza in Dzibanché, Alexander Tokovinine – allude to ancestors who seem to inhabit the night sky, with stars, snakes and other motifs typical of Mayan and Teotihuacan iconography.

“In this relief, the absence of a central sculpture is also noticeable, so it is not ruled out that the two missing effigies were removed, centuries ago, by the city’s own inhabitants. Meanwhile, the third scene shows a set of mythological animals associated with constellations.”

Archaeologist Sandra Balanzario Granados, head of the Archaeological Site Improvement Program in Dzibanché, said: “This is a great finding for us. Although we had [found] stucco reliefs on larger buildings, we would never have thought of finding such decorated façades on a ballcourt with such profound meanings as these ones apparently have.”

Professor John W. Hoopes directs the Global Indigenous Nations Studies Program at the University of Kansas. He is an expert in the pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures in Latin America.

Professor Hoopes told The Express: “There are clear associations of ballcourts with sacrifices. The Kiche’ creation story in the Popol Vuh makes direct references to ballgames and human sacrifice.

“In 378 CE, a group of warriors from Teotihuacán in central Mexico entered the Maya lowlands and successfully overthrew the leader of Tikal. Several Maya sites now show that their royal dynasties had ties to Teotihuacán.

“Snake imagery is common at both Teotihuacán and in the Maya area. The sky imagery is especially interesting because both cultures were interested in astronomy. Animals were significant for both. The sky was regarded as Xibalba, the Underworld.

“Dzibanché was an important early centre for the origin of what became the ruling dynasty of Calakmul, a rival city of Tikal.”

But what did INAH mean by “ancestors who seem to inhabit the night sky”?

Professor Hoopes said: “One interpretation is that Maya kings became celestial objects after they died: the Sun, Moon, Venus, Mars, etc. The Maya king going into the sky is the theme of the Sarcophagus Lid at Palenque.”