The window on the fifth floor of a building in the historic city of Petrozavodsk in northwestern Russia was wide open when the figure of a man appeared briefly, before plunging to the ground. The crushed body of former police colonel, Artur Pryakhin, head of the Federal Antimonopoly Service in the republic of Karelia, was carted off to the mortuary. Another “suicide” was listed by the Russian authorities.

In the West, it has become a common observation that Russian officials who fall out of favour with the Kremlin should not stand by open windows in high buildings. Pryakhin, whose death was registered in February, was one of an estimated 17 Russian officials, politicians, businessmen and leading figures in the arts whose death followed similar falls from high windows in the last 30 months alone.

While the authorities were generally quick to blame suicide or accidental deaths, open-window syndrome has become part of the lexicon of fear in a country where the rule of obedience and loyalty is rigidly enforced from the Kremlin.

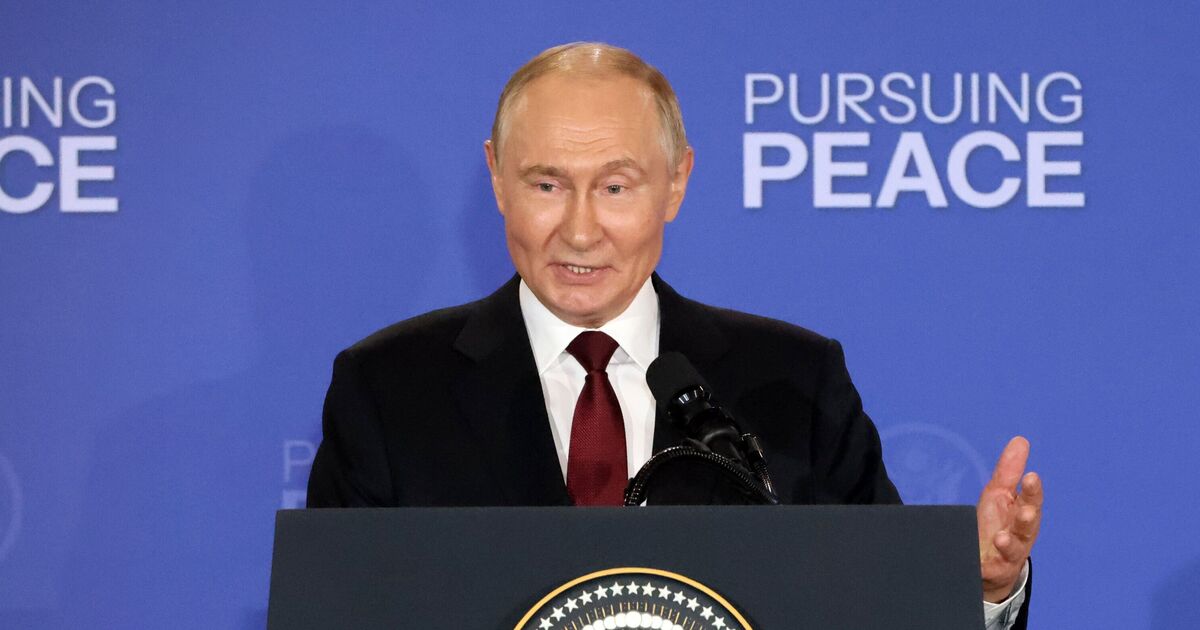

Vladimir Putin, leader of Russia for more than 20 years, has been ruthless in dealing with his political opponents at home. He has also publicly warned that anyone who dares to betray the motherland by spying for the West will be hunted down wherever they may be, at home or abroad, and face elimination.

In 2022, Putin made a speech in which he spelled out what he feels about Russian nationals who betray their country. He referred to them as “scum and traitors”. Patriots, he said, would “simply spit them out like a gnat that accidentally flew into their mouths, spit them out on the pavement”.

It was this warning of extra-judicial extermination that drove me to write a series of spy thrillers based on the premise that the highest echelons of the Russian government had the president’s authority to launch sabotage and assassination missions around the world against Western interests. But also, specifically, they could target anyone who deserved punishment by death for disloyalty.

The 17 public figures who have plunged from open windows since December, 2022, include Andrei Badalov, vice president of Transneft, a state-controlled pipeline transport company, who fell from a window of his home in a Moscow suburb in July; and Vadim Stroykin, a singer who had criticised the war in Ukraine in social media posts, who fell from a 10th-storey window during a police search of his apartment in February.

Last year, deaths from window falls included Alexander Lupin, former head of Krasnoyarsk’s landscaping and green construction authority who, on December 11, fell from a seventh-floor window while being interrogated by police for corruption; and, on February 15, 2023, Marina Yankina, head of finance and procurement at the defence ministry’s western military district, plunged from the 16th floor of her apartment building in St Petersburg.

In a different apparent “suicide” on July 7 this year, Russia’s transport minister Roman Starovoit, was found dead from a gunshot wound in his parked car hours after the Kremlin announced he had been fired by Putin.

The deaths, whether self-inflicted or not, demonstrate that public figures in Russia can be vulnerable if their loyalty to the state comes into question. The purpose of my novel was to highlight how life and death in Russia are in the hands of a regime which does not hesitate to seek revenge if and when required.

The evidence is abundant: in November, 2006, Alexander Litvinenko, a naturalised British defector, ex-member of Moscow’s federal security service (FSB) and fierce critic in exile of the Kremlin, was notoriously poisoned in London with radioactive polonium-210 and died in hospital of heart failure. Two former Russian intelligence agents had tea with Litvinenko at a hotel in London when he ingested the poison, Met Police detectives discovered.

In March, 2018, Sergei Skripal, a former Russian military intelligence officer who was a double agent for MI6 during the 1990s and early 2000s and had been involved in a spy exchange between Moscow and London following his conviction for treason, was poisoned with Novichok nerve agent. The deadly agent had been smeared on to the handle of his front door in Salisbury. His daughter, Yulia, was also poisoned.

Both miraculously survived. So, too, did a police officer who was contaminated with the nerve agent. But in a separate poisoning incident in Amesbury, near Salisbury, three months later, a perfume bottle was found in a charity bin. Mother of three Dawn Sturgess, 44, sprayed some of the “perfume” on her wrists. The liquid was Novichok and she died.

Two members of the Russian GRU military intelligence agency, who had been spotted in Salisbury, were identified as the main suspects but they had returned to Moscow and total impunity. The Kremlin said the “suspects” were civilians and denied any involvement in the Novichok poisonings.

The long arm of Russia’s intelligence services is a good basis for a spy thriller. In my novel Shadow Lives, published in 2022, a GRU officer, Mikhail Gerasimov, comes in disguise to London to assassinate the female director of MI5’s counter-espionage branch, in revenge for the expulsion of Russian spies from the UK.

He meets Rebecca Strong, a commercial artist, and they strike up a relationship. Ignorant of his real identity, she becomes innocently immersed in the Russian’s plot. Gerasimov aborts his mission when he can’t bring himself to shoot a woman in cold blood.

In my recently published sequel, Agent Redruth, the GRU officer recently promoted to a highly sensitive job in the Kremlin, makes a big decision – to offer his services to British intelligence as a double agent because of growing disaffection with Putin over the war in Ukraine. He contacts Rebecca Strong to get the ball rolling.

When he becomes a suspect in Moscow, following a series of intelligence leaks, Rebecca – now an unofficial, paid-up member of MI5 – is forced to try and rescue him from the clutches of a pursuing FSB investigator.

Since the Skripal assassination attempt, it emerged that a special team of Russian saboteurs and assassins had for years been roaming Europe in search of traitors and critics of the Putin government. Called Unit 29155, it consisted of veteran GRU members with years of experience of fighting in Afghanistan, Chechnya and Ukraine.

It was believed Unit 29155 was responsible for the assassination attempt on Sergei Skripal. The unit was also thought to have been behind the attempted poisoning in 2015 of a Bulgarian arms dealer called Emilian Gebrev.

Today, a new unit of saboteurs has been established, called the Russian Department of Special Tasks, based at GRU headquarters in Moscow, according to a report in The Wall Street Journal in February.

Known as SSD, it was set up in 2023 in response to Western support for Ukraine after the Russian invasion on February 24, 2022. Western intelligence services believe SSD has replaced Unit 29155 as the prime GRU organisation responsible for carrying out subversive missions in Europe.

Shadow Lives, Agent Redruth, and a nearly-completed third in the series, to be called Spies from Moscow – which has a dozen Russian GRU agents arriving in Britain to assassinate the now defected Colonel Mikhail Gerasimov – are fictional.

However, they all tell a story that could have been taken straight from the files of the Russian GRU military intelligence service.

- Agent Redruth by Michael Evans (Rowanvale Books, £11.99) is out now